The Real Poverty Line

The official poverty line masks how vulnerable households really are. With soaring housing, healthcare, and childcare costs—plus a monetary system that inflates asset prices—more families depend on subsidies just to get by. Is bitcoin an unexpected way out?

Erik

If you were scrolling through X last week, you probably came across Mike Green's article My Life is a Lie. In the piece that went viral, Green argues that a much larger group of Americans are effectively 'working poor' than official figures suggest. What's his reasoning, how does this compare to the Dutch situation, and what does it have to do with our monetary system?

Brilliant article by @profplum99 - I don't think this could have been articulated anyway possibly better.https://t.co/UpG6MwvmiM

— Swingtrader (@Swingtrader) November 23, 2025

Flashback to the 1930s. My great-grandfather, a well-read coal miner, wanted to prevent his son from being condemned to a life underground. He made sure my grandfather got his bookkeeping diploma. My grandfather chose the mine anyway (fortunately in an above-ground role), to avoid being sent to work in Nazi Germany, and because 'the pit' paid well. On his salary alone, he and my grandmother bought a house in post-war Limburg and raised four children.

If he were still alive, my grandfather might be surprised that it's extremely difficult for my wife and me to buy a house in a Utrecht suburb on two incomes, even though we have nothing to complain about financially. The aforementioned Mike Green writes a series of articles on this subject. In the first article My Life is a Lie, he begins with the quantitative basis for the American poverty line.

The outdated benchmark of the poverty line

His main point is that the definition of the so-called poverty line wrongly gives the impression that anyone earning more is comfortably getting by. And that this causes an underestimation of how many Americans struggle with financial security.

The poverty line was introduced in the US in the early sixties as three times the cost of a minimum food budget. Since then, this benchmark has only been adjusted for consumer price inflation. Today, an American family needs at least $10,400 per year for food, which puts the current official poverty line at $31,200.

But the cost structure of the American household budget has completely changed. Food has become relatively cheap, while housing, healthcare, and childcare now take a huge bite out of the budget.

Green does the math and determines the actual minimum budget for an American family with two children. He arrives at a figure of, brace yourself, $118k per year.

These are the main expenses for an American family:

- Childcare: $33k

- Housing: $23k

- Food: $15k

- Transportation: $15k

- Medical expenses: $11k

- Other essentials: $22k

While such a family won't immediately go hungry if it (temporarily) loses income, it will struggle to remain connected to society. That's why $118k is what Green calls the "survival line": below that threshold, you structurally struggle to finance housing, childcare, healthcare, and transportation while participating in society.

His point is that because the poverty line is set far too low, it appears as though poverty has been pushed back and "the system works." In reality, a large portion of the population lives below the level at which you can participate on your own strength, trapped in a situation where working more yields little or nothing extra.

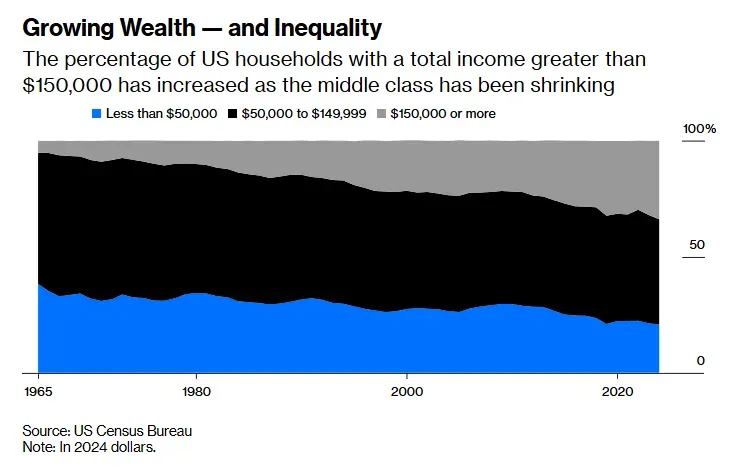

Green on the chart above:

The economists look at this and cheer. "Look!" they say. "In 1967, only 5% of families made over $150,000 (adjusted for inflation). Now, 34% do! We are a nation of rising aristocrats." [...] This chart doesn't show that 34% of Americans are rich. It shows that only 34% of Americans have managed to escape deprivation. It shows that the "Middle Class" (the dark blue section between $50,000 and $150,000)—roughly 45% of the country—is actually the Working Poor.

The usual interpretation of that chart is: 21% are poor, 45% are middle class, and 34% are wealthy. According to Green, that's a misrepresentation. It should be: 21% are at the poverty line, 45% are in the transition zone, and 34% can fully and independently participate in society.

In that transition zone, you can earn more by working hard and getting promoted, but you don't keep more. For every extra dollar you earn, a dollar of support disappears. Only well above $100,000 per year does gravity lose its grip and do you escape the Valley of Death.

A reasonable objection is that we live much more luxuriously than in the sixties. What do we have to complain about? Better cars, Netflix, a mobile phone... Sure, but where a $5 phone connection used to be enough to participate in society, now you need a mobile phone. Even after adjusting for inflation, it's much more expensive. Many so-called luxury goods are pure necessities; if you lose them, you can no longer function.

The Dutch situation

In the Netherlands too, the differences with the sixties are significant. Food takes up a smaller share of the budget, while housing, healthcare, and childcare have become heavier burdens. An important difference from the US is that the Valley of Death here is less deep and less steep.

Just like in the US, we have the 'poverty trap' where people who start working (more) barely have more (or even less) to spend. And we also regularly hear experiences from people who, during the journey from a low to a high income, actually make little progress.

But in the Netherlands, there's much more attention to this than in the US. We've been fine-tuning 'marginal tax pressure' for decades to ensure that working more pays off at least a little. The government regularly reports on this to parliament. In September, it concluded that "84.6% of workers have a marginal pressure of 60% or lower." So they keep 40 cents of every extra euro earned.

The Nibud and SCP use a poverty threshold of €2,535 disposable income per month for a family with two children. That's important: benefits are already factored into that amount. Housing benefits, healthcare allowances, child-related budget, and childcare allowances all count as income before assessing whether a household is 'poor.'

That amount is the lower boundary of the transition zone in the Netherlands. From there begins the journey to the level where you can fully participate in society without support and allowances. Working more hours, a working partner, a promotion, a second job – all ways to generate more income. But it's hard work to increase your disposable income. While life becomes busier, more stressful, and more complex.

Our money is broken

Green's piece is the first in a series. It outlines the problem but barely discusses solutions or causes yet. That's understandable. It's a thorny issue, rooted in major secular changes over the past 75 years, such as demographics, globalization, and the accumulation of government debt.

One example. Globalization has generated enormous wealth growth in emerging economies. Poverty, infant mortality, and hunger have declined dramatically. But at the expense of the middle class in developed economies like the US and Europe – the group Green is talking about.

We hope Green addresses these big themes in future installments, with an eye for the role of the monetary system itself. Because its design matters.

In the current design, growth is so important that governments accept inflation and rising debts. With the result that the 'haves' watch the value of their assets grow without any effort, while the 'have-nots' have to work harder and harder just to get a seat on the train.

In Ons geld is stuk (Our Money is Broken), the Slagter brothers wrote extensively about how the design of the monetary system shapes society and the economy.

That brings me back to my grandfather, who lived in a time when the working class could still buy a house on a single income. I imagine his puzzled expression if I could explain to him that buying a small house in 2025 is beyond reach on our two incomes.

But don't worry grandpa, we're investing in our future by saving in software code designed by an anonymous programmer. Everything will be just fine!

More Alpha

Are you a Plus member? Then we continue with the following topics:

- FUD: Tether season has opened again

- The ECB sees stablecoins as a risk

- Real-world assets are the fastest grower after stablecoins

1️⃣ FUD: Tether season has opened again

Peter

There are moments in the crypto market when you notice the cycle has begun a new round. Sometimes it's an ETF. Sometimes a political statement. And every once in a while: Tether. It starts with one tweet from someone with a recognizable face, a few big accounts pile on, and suddenly the rumor mill is churning again. This time it was Arthur Hayes who lit the fuse.

The Tether folks are in the early innings of running a massive interest rate trade. How I read this audit is they think the Fed will cut rates which crushes their interest income. In response, they are buying gold and $BTC that should in theory moon as the price of money falls.… pic.twitter.com/ZGhQRP4SVF

— Arthur Hayes (@CryptoHayes) November 29, 2025

Hayes looked at the latest Tether figures and concluded that the company is preparing for falling bond yields. His reasoning: Tether currently earns absurd amounts from short-term US debt. But when the Fed cuts rates, those revenues will partly disappear. Therefore, Hayes writes, Tether is shifting part of its reserves toward gold and bitcoin – assets that will "moon" when money becomes cheaper. Just one problem: USDT's collateral starts to wobble if those positions drop thirty percent in value. Tether would then be "theoretically insolvent." "Grab the popcorn," Hayes advises, expecting major media to pile onto this story.

Within a few hours, half of Twitter was in the stands. One half with the familiar refrain. Tether is junk, a house of cards, a systemic risk with a marketing department. The other half shrugged. Nothing new, nothing alarming, nothing to lose sleep over.

As usual, the truth lies somewhere in between.

Anyone who looks at the figures themselves sees a familiar structure. About $140 billion of the reserve sits in super-boring, ultra-short-term US Treasury securities, money market funds, and repos. That's the safe, liquid core. Tether earns about five to six billion dollars annually on the interest. And because Tether is a relatively small and efficient company, a large portion of that remains as profit. That quickly provides a buffer that many traditional banks would be jealous of.

Then there are the riskier positions. About $10 billion in bitcoin, nearly $13 billion in gold, and over $14 billion in loans extended by Tether. All together, that's roughly twelve percent of total reserves. Not small, but not an all-determining leverage either. And importantly: those positions were almost all purchased from profits, not from newly issued USDT.

Hayes's point – that a hefty drawdown would punch a hole in the reserves – is theoretically correct. But it's a paper observation in a world where Tether runs a business that produces billions in cash flow every quarter. A former Citi analyst wrote that Tether's non-public corporate balance sheet probably contains even more value: investments in companies, mining activities, additional BTC. Anyone looking only at the reserve balance misses another important part of the company.

I spent 100's of hours writing research on tether for @Citi. @CryptoHayes missed a few key points.

— Joseph (@JosephA140) November 30, 2025

1) 𝐓𝐡𝐞𝐢𝐫 𝐝𝐢𝐬𝐜𝐥𝐨𝐬𝐞𝐝 𝐚𝐬𝐬𝐞𝐭𝐬 =/ 𝐚𝐥𝐥 𝐜𝐨𝐫𝐩𝐨𝐫𝐚𝐭𝐞 𝐚𝐬𝐬𝐞𝐭𝐬

When tether generates $ they have a separate equity balance sheet which they don't… https://t.co/pHSRr245Up

And yet. Despite all that relativizing, one question keeps nagging: why still no proper audit? The BDO paperwork is not an audit, not an IFRS annual report, and not a complete examination. It explicitly states that: the document follows its own accounting policy, provides no insight into stress scenarios, and is merely a snapshot. The auditor even says the valuations assume "normal market conditions" – precisely the conditions that disappear when things actually get tense. It's competent work, but not ultimate certainty.

And that's where the systemic risk pinches. You don't have to be a Tether truther to think that a private issuer of 181 billion synthetic dollars should publish an audit. Not because Tether is necessarily rotten, but because trust in infrastructure shouldn't depend on the mood on Twitter.

There's something else too: Tether increasingly behaves as if it's building its own monetary order. Four days ago, the Financial Times wrote about Tether's gold hunger. The company now owns 116 tons and is one of the largest gold holders outside central banks. The massive purchases even explain part of the recent gold rally. As if the company is preparing for a world where gold and bitcoin form a counterweight to the dollar system. That makes it fascinating, but also complicated. Because an alternative system requires more transparency, not less.

The crypto industry is now competing with central banks for gold:

— The Kobeissi Letter (@KobeissiLetter) November 28, 2025

Tether purchased +26 tonnes of gold in Q3 2025, surpassing all official central bank buying.

In comparison, Kazakhstan acquired +18 tonnes, Brazil +15 tonnes, and Turkey +7 tonnes.

As a result, Tether's gold… pic.twitter.com/hCcIhs2dS3

Anyway, the market needn't be afraid. There's no explosion imminent, and the figures show a company making money at an eyebrow-raising pace. But it remains a black box, and black boxes don't become dangerous because they're empty, but because nobody sees what's happening inside.

Only a real audit will extinguish the ghost story. Until then, Tether FUD remains a recurring ritual: predictable, sometimes tiresome, but impossible to ignore.

2️⃣ The ECB sees stablecoins as a risk

Peter

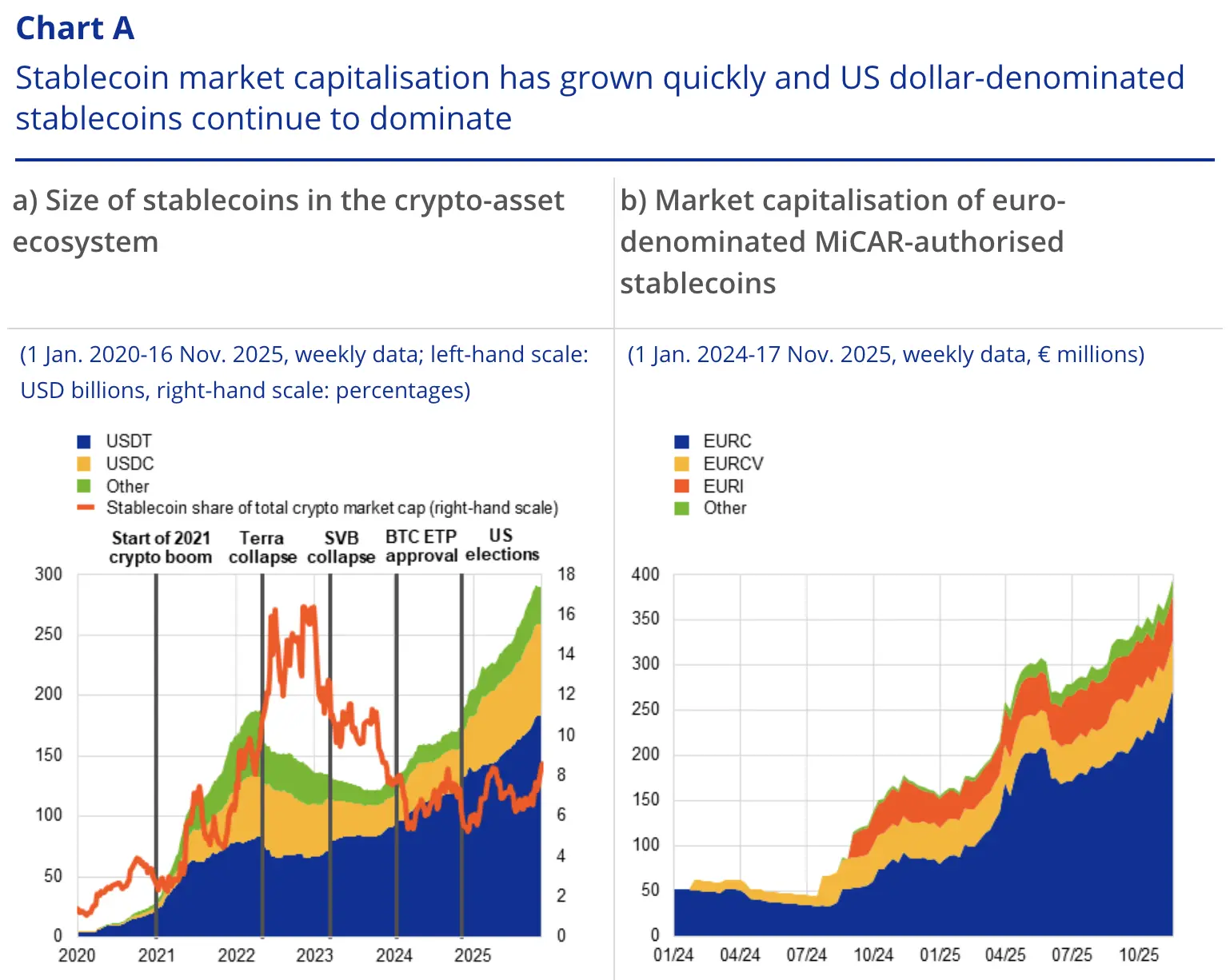

The European Central Bank published a new chapter in its Financial Stability Review this month, shining the spotlight on an old acquaintance: stablecoins. According to the ECB, the market has now grown to over $280 billion, with Tether (USDT) and USD Coin (USDC) as the main players, together accounting for 90% of the total. Euro stablecoins? They exist, but remain noise in the margins.

The facts aren't in dispute. Stablecoins are big, growing fast, and facilitate billions in money movement outside the traditional system. The ECB rightly identifies the potential risks. A run on a stablecoin could lead to large-scale selling of government bonds, disruption of market liquidity, and even destabilize banks.

But what the report primarily shows is the fear of something else: savings leaking away to alternatives outside the banking system. People moving away from 1% savings rates. Away from negative real interest rates. Away from a sector that relies on privileges and implicit state guarantees. That concern is so great that the ECB writes it without embarrassment: stablecoins may not offer interest under MiCA, because that would accelerate the outflow of bank deposits. Households must stay in the system. Period.

With that, the ECB says out loud what it's really about. The banking cartel must be protected, as must control over monetary instruments – the strings that central bankers hold. At this moment, the ECB doesn't yet see acute risks, but because the infrastructure of alternatives is growing rapidly, things could move fast. The problem isn't the size, but the precedent.

It's ironic, but not unexpected, that the ECB leaves another precedent undiscussed. What if the stablecoin isn't the problem, but the collateral it's based on? What happens if trust in government bonds erodes further – not because of crypto, but because of the state of public finances? When markets worry about higher debts, rising deficits, or political meddling? In that scenario, stablecoins aren't looking into the abyss – they're reflecting it. They're not the fuse then, but the barometer.

As soon as alternatives like stablecoins, gold, or bitcoin become attractive, central bankers have to show their hand. Then it becomes visible that the traditional system depends on financial repression. Keeping capital inside, keeping rates low, restricting alternatives, and hoping nobody yells 'fire' in the theater.

The ECB sees stablecoins as a risk. But stability doesn't come from blocking savers. It comes from trust – and that's the one thing the system is running short on.

3️⃣ Real-world assets are the fastest grower after stablecoins

Peter

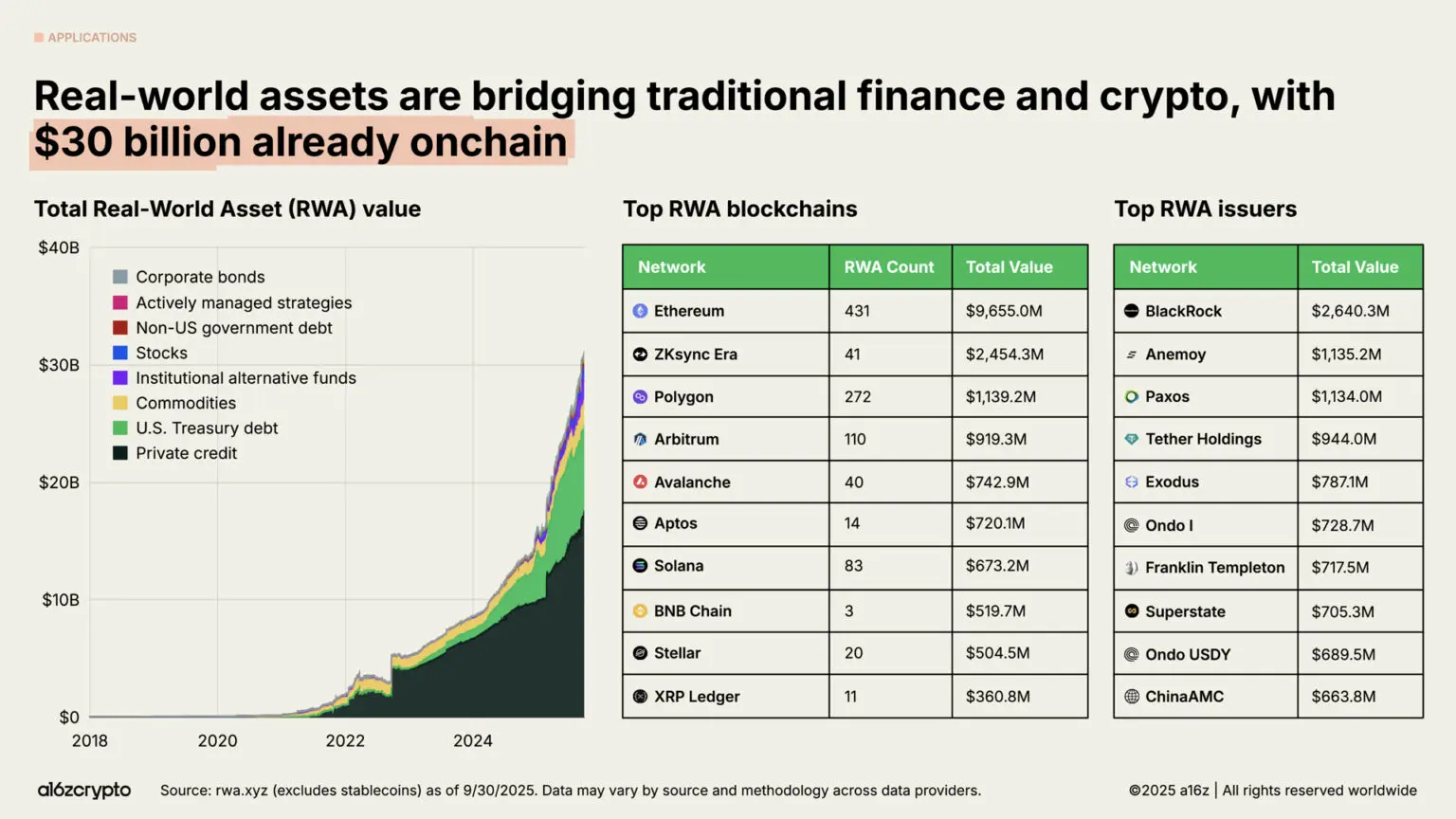

Real-world assets (RWAs) are ordinary financial products in a new wrapper. Government bonds, money market funds, private credit: everything that keeps the traditional market running, but as a token on a blockchain. Instead of PDFs, settlement delays, and expensive intermediaries, you get a digital proof of ownership that can be moved 24/7.

The popularity of these tokens is becoming visible. RedStone wrote in its On-chain Finance Report that there's now over $30 billion in RWAs on-chain. Two years ago, that figure was still under $8 billion. The largest portion comes from private credit – loans to companies raising capital outside the stock exchange – followed closely by tokenized debt securities. US Treasury bonds in particular are a hit: stable yield, clear regulation, and the kind of collateral DeFi needs to attract activity.

RedStone nicely shows why this is happening so fast. Demand for safe and predictable yield is high, and RWAs suddenly make it simple to use such assets in on-chain markets. You see the same picture in a16z's State of Crypto Report 2025: they also value the RWA market at around $30 billion and call it "the bridge" between crypto and the established financial world. Not as a metaphor, but because parties like BlackRock, Franklin Templeton, and Paxos now manage RWA funds themselves.

It doesn't stop at fund houses. Even Nasdaq has now filed a proposal with the SEC to offer listed shares as tokens. Their head of digital assets emphasized they "don't want to overthrow the system," but finally make it more efficient – precisely the line you see across the entire sector. The pace at which the traditional market is now getting on board really says it all.

And you can tell. Tokenized Treasuries are increasingly used in on-chain money markets, private credit flows through platforms like Clearpool and Maple without the sluggishness of the traditional credit chain, and infrastructure players like Chainlink and RedStone provide the valuation data that keeps it all running. It's starting to look like an ecosystem.

Of course: $30 billion is peanuts compared to the $100 trillion in traditionally issued bonds. But that's precisely why it's interesting. If even a fraction of that moves to the DeFi world, tokenization is no longer a niche but a standard.

For now, the main conclusion is simple: RWAs have left the playground. This is a market that's beginning to mature, where traditional parties are no longer spectators but setting the tone.

🍟 Snacks

To wrap up, some quick bites:

- Klarna tests its own stablecoin on Stripe's blockchain network Tempo. The BNPL giant launched KlarnaUSD on Tempo's testnet, aiming to make dollar payments faster and cheaper in the long run. The company sees its stablecoin primarily as new infrastructure for cross-border transactions, not as a consumer product. If the pilots succeed, KlarnaUSD will officially launch in 2026. Klarna has 114 million customers, collectively handling $118 billion in payment volume.

- Green light for Polymarket's return to the US market. The on-chain prediction market received approval from the CFTC this week, after acquiring the regulated trading platform QCX this summer. This allows Polymarket to legally serve American users again. Analysts see it as a breakthrough: for the first time in years, the regulator is choosing to allow prediction markets rather than ban them.

- Sony Bank is working on its own dollar stablecoin for games and entertainment. According to Nikkei, the bank wants to use its own digital dollar for payments within Sony's ecosystems starting in 2026 – from PlayStation to anime platforms. Sony applied for a US banking license in October through its newly established subsidiary Connectia Trust.

- Strategy will only sell bitcoin as a last resort, says CEO Phong Le. For example, if the mNAV – the market value of the stock relative to the bitcoin value on the balance sheet – drops below 1 and it can no longer raise new capital. According to Le, selling bitcoin would then be "mathematically justified," in defense of what he calls "bitcoin yield per share." Le emphasizes there are currently no concrete sale plans.

- Kazakhstan's central bank considering major investment in cryptocurrencies. The National Bank of Kazakhstan is thinking about a position of up to $300 million in digital assets, according to RBC. On November 28, NBK chairman Timur Suleimenov announced the idea during a press conference. Due to the recent market correction, the bank is "waiting for the dust to settle" before entering. The money would come from the central bank's currency reserves, not from the national sovereign wealth fund.

- China reaffirms hard ban on crypto and stablecoins. In a meeting on November 28, the central bank again stated that digital assets are not legal tender and that trading and use in the market remain illegal. According to Beijing, stablecoins pose extra risks around KYC and capital flight. The message remains strictly unchanged: controlling risks comes first, and the crypto ban stands proudly intact.

Thank you for reading!

To stay informed about the latest market developments and insights, follow our team members on X:

- Bart Mol (@Bart_Mol)

- Peter Slagter (@pesla)

- Bert Slagter (@bslagter)

- Mike Lelieveld (@mlelieveld)

We appreciate your continued support and look forward to bringing you more comprehensive analysis in our next edition.

Until then!